A legacy-driven media platform documenting Korean excellence in culture, economy, and identity

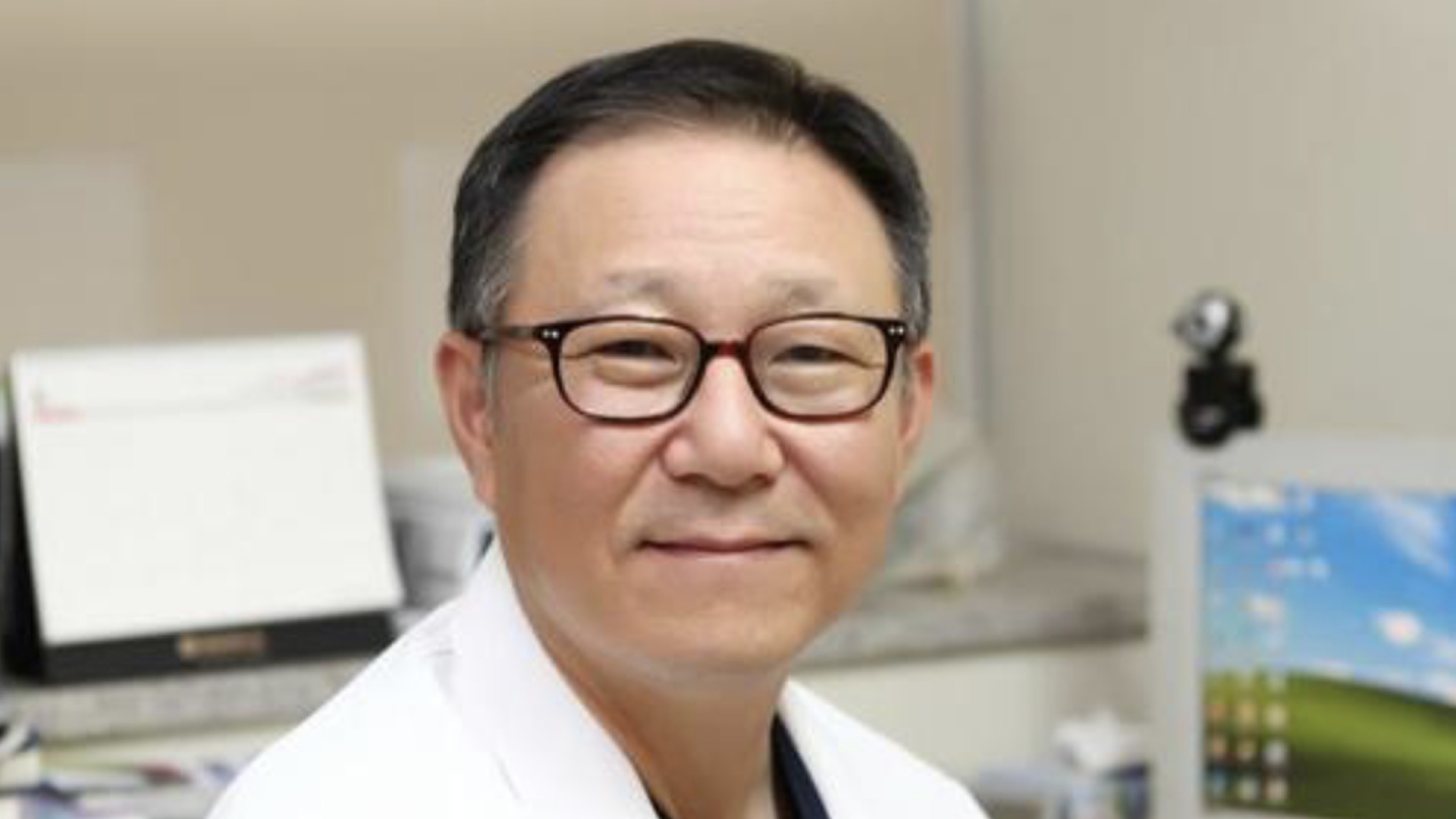

33 Years as a Neurologist: A Life in Neuroscience

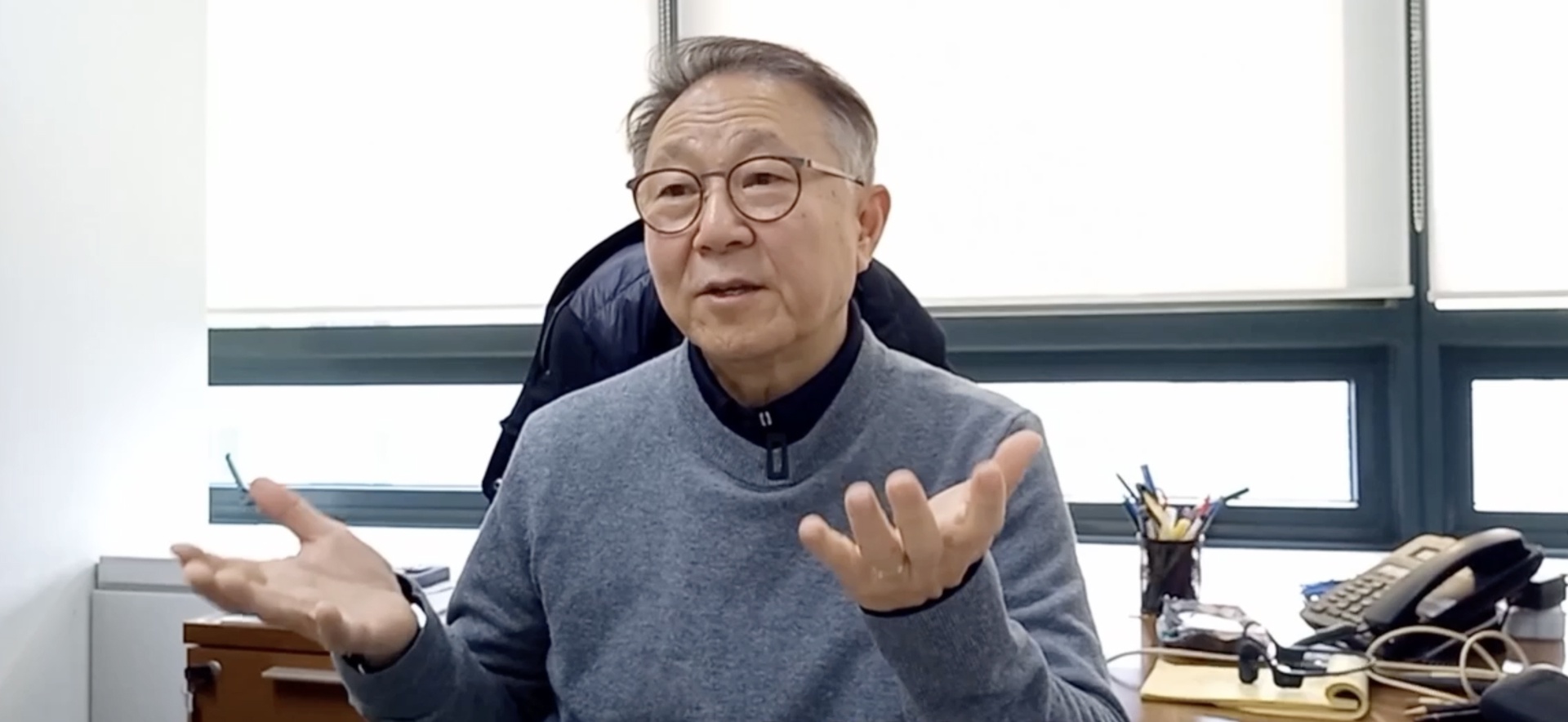

Q: You’ve been active in the medical field for decades. Can you share your journey as a doctor and professor?

I entered medical school in 1978 and graduated in 1984. After completing my military service, I earned my neurology specialization in 1998. I began teaching at Soonchunhyang University Hospital in 1991 and have spent the past 33 years treating patients and pursuing research. I chose neurology because I anticipated Korea’s aging population, and conditions like stroke and dementia would become major issues. At that time, neurology was still a developing field, and I saw great potential in contributing to its growth.

Q: What led you to focus specifically on dementia research?

Initially, I concentrated on stroke studies. About ten years ago, my focus shifted to dementia. While running the Yongsan-gu Dementia Relief Center, I saw how critical prevention and early management are. Later, I served as president of the Korean Dementia Association, becoming involved in national policy and advisory roles. Dementia is not just a personal illness—it affects families and society as a whole. As cases rise, so do caregiving burdens and social costs. Notably, we’re now seeing early-onset symptoms in younger people, which makes lifestyle changes and early screening essential.

Q: How is Korea tackling dementia on a governmental level?

Since 2010, Seoul has operated Dementia Relief Centers, which have now expanded nationwide. These centers offer early risk screening, education, and treatment access. The government also subsidizes brain scans and medication costs post-diagnosis. As a result, Korea’s dementia model is seen as globally forward-thinking. But public policy alone isn’t enough. Individual awareness and preventive action are equally vital.

Q: Is there hope for treating or curing dementia?

Currently, complete cures are rare. The focus is on slowing progression. Existing drugs help manage symptoms by adjusting neurotransmitters. Recently, a new class of medications that slow disease advancement was approved by the FDA in the U.S., and similar treatments are being introduced in Korea. These are under review for insurance coverage. Beyond medication, regular exercise, reading, music, and learning new languages have all shown positive effects on brain resilience.

Q: How does sleep affect cognitive health?

Sleep plays a vital role. During sleep, the brain clears waste products. Poor sleep quality or disorders like sleep apnea significantly raise dementia and stroke risk. Those who snore or experience breathing issues at night should consider a sleep clinic. Wearable devices now help track sleep patterns, and consulting a specialist is recommended for ongoing issues.

Q: What challenges do Korean immigrants in the U.S. face in dementia prevention?

Social isolation and language barriers can accelerate cognitive decline. In many Korean American communities, getting tested is difficult due to a lack of Korean-language support. This has led some elders to even consider returning to Korea for care. There’s a growing need for accessible, culturally competent diagnostics and care options in the U.S.

Q: Korea’s expanding medical school quota has sparked debate. What’s your take?

Simply increasing numbers isn’t enough. We need structural support for underrepresented but essential fields like OB-GYN, pediatrics, and thoracic surgery. Many students avoid these areas. The government must offer incentives and support systems that guide medical students toward these critical specialties.

Q: How does Korea’s national health system compare to America’s private insurance system?

Korea’s universal healthcare ensures strong medical accessibility. In contrast, the U.S. system relies heavily on private insurance, which often results in high costs and bureaucratic delays. Korea’s challenge is sustaining this model long-term through better funding and more efficient resource allocation.

Q: Any advice for our readers on keeping their brains healthy?

Exercise regularly, get quality sleep, and stay socially engaged. Meet with friends and family often, and seek out new hobbies. Most importantly, schedule routine checkups to catch issues early. Prevention is the best medicine for the brain. With steady care and curiosity, we can age with clarity and connection.

Dr. Ahn reminds us that dementia is no longer something to fear—it’s something we can manage and prevent with knowledge, attention, and action. From reading to conversation, every small habit can be a powerful tool for brain health. Investing in memory isn’t just personal—it’s a long-term act of care, for ourselves and for those who love us.